The walls of his on-campus office are adorned with posters of French book covers and Kandinsky art. His desk displays stacks of French literature and philosophy textbooks, handmade trinkets and circuit boards and research for his work uncovering his father’s past as a French diplomat.

Northeastern tenured French and philosophy professor, amateur music composer, handyman and photography enthusiast, Holbrook Robinson is a busy man who, when asked, described himself as grateful.

“I am an extremely lucky person: being raised by people with outstanding qualities, being endowed by my genetics with multiple interests and in some cases the capacities needed to tend to them, having a childhood rich in formative experiences, being fortunate to have a job I love, working with people I respect, the chance to meet exciting, vital young people every day of my working life, and living in a part of the country that I like,” he said.

The 72-year-old Robinson said he has been hard at work to discover his father’s life story. Robinson was born in 1943, the youngest of three, in Lancaster, Pa. In 1948, at the age of five, his family moved to Sweden for a year while his father worked as a diplomat for the Swedish Embassy. In 1952, after being back in Lancaster, the Robinson moved again, this time to France, where he spent the next four years with his father working at the French Embassy. Robinson said he remembers moving to these different countries quite clearly, even though he was little. He described France as being very different than provincial Pennsylvania, where they moved back to when Robinson was in eighth grade.

As a child, Robinson knew that his father left the French Foreign Service, but he and his family never knew why. Through extensive and continuing research, he has discovered that his father was discharged in1956 potentially for homosexual notions or communist sympathies. Robinson said he has been able to gather research through the U.S. archives, communications with the President’s office, and phone calls with authors of books on similar topics. His research even led him to find the exact memo that was written in the exit interview with the man who discharged his father. He described his research as a detective story, making intense discoveries after extensive research, only to lead him down another path. Robinson said he hopes to meaningfully chronicle his father’s story in a book or article, including how his father’s career affected him as a child in France.

When the Robinsons returned to the United States, Robinson said it took time to get used to being back in American schools. He said he saw French schools as very different and more demanding than American schools. Robinson said he was able to excel in classes thanks to school in France, but his only weak subject was English, since he had spent so long writing in French.

At the start of high school, Robinson moved to Long Island. From there, he went on to Princeton University as a philosophy major.

“Princeton was an odd place”, Robinson said. “At that time, the American elite were coming to Princeton, and I realized then that I did not like that social class.” Despite that, Robinson felt as though he profited a lot from his Ivy League education, and continued to graduate school at Harvard to get his doctorate in French literature. His bottom shelf holds up his big black book of his dissertation on Ramon Fernandez, French philosophical literary critic, and his work with the Germans during the French occupation. He joked that no one has read it, but it was still a big accomplishment in his early career. While he did not know it at the time, the work he was doing at this time would provide him lot of the background to learn about what was going on in his father’s life in France in the 1950s.

Robinson got married in 1966 and moved to his current home in Cambridge. He started working at Northeastern in 1969, after his wife encouraged him to find a summer job. At the time, Northeastern was not offering any summer positions but was able to hire him for the winter. Robinson described the school then to be very different than today. “Northeastern then was a real dump, none of the buildings were neat, and the reputation was a determinedly working class school, where people came if they didn’t have enough money to go to other places,” he said. But he immediately liked it. “It had a really neat vibe and the students I had then were really wonderful. I was tired of Ivy League entitlement, and so Northeastern was a real breath of fresh air,” he said.

And now, he’s still here. While Robinson admits that it is very different than the “olden days”, he said he is very devoted to the school. “My very good students really like it here, so I think it would be an interesting place to be a student. There’s so much variety and a lot of good energy on campus,” he said. He said he feels lucky to work here at a university where teaching is more than just a job to him. The setting, the wide variety of students, the coop mission and the respect he feels make his time worthwhile at Northeastern, and he has always felt like he has a voice, he said.

Freshman, Deva Goosen is taking Robinson’s class this semester called Introduction to Language, Literature, and Culture. She said she enjoys the class because it is full of discussion, making it feel less like a lecture. “Students are aware that he is willing and interested in listening to our opinions. During discussions he offers up what he believes and thinks about certain topics and he doesn’t assume that his opinion is right or superior over ours,” Goosen said, “It creates an active and open classroom in which I value.”

Now, as a tenured professor, Robinson is enjoying the freedom to develop in new intellectual ways, while still enjoying teaching and often developing new classes to teach. “I have about two classes each term, which gives me great freedom to explore other research projects and ideas, nothing like a ‘9-5 job’,” he said. At Northeastern, he has taught French language and literature classes, classes on specific French authors and existentialism. In the philosophy department, he has taught introductory classes, philosophical aesthetics, and even created several courses on unique topics including the German occupation of France as seen through film.

While other people his age may be thinking of retirement, Robinson has his eye on other goals for his future. Robinson said one of his greatest passions is composing classical music. While not a musician himself, Robinson is able to use computer technology to write and listen to scores of his own music that resemble the types of classical music that he enjoys listening to. So far, he said he has written 24 scores, some for strings, others for piano, and one of his goals right now is to have his music played by real people.

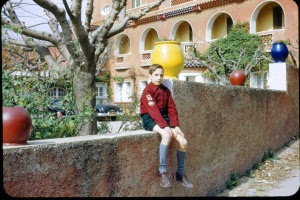

He also has camera and lens collections that explain his other passion: photography. He said he loves taking pictures and has kept all the collections of his parents’ picture albums. Robinson described tracking down the location of his father’s first color photograph, a picture of young Robinson sitting on a wall in Bandol, France on his 10th birthday. As an adult, Robinson and his nephew traveled back to Bandol and found the same wall, with the same tree in the background. He took an imitation of the same picture, several years later, sitting in the same exact position as when he was 10.

When asked what he was most proud of, Robinson said “the fact that I actually wrote about music after dreaming about doing it for so long.”

But Robinson said he is also proud of his beautiful remote control sailboat that he built, the real sailboat he restored and now owns, and his ability to fix anything from boats to plumbing and flooring at his house, to circuit boards. “These are all things I’ve always loved, even though I never chose to like what I like,” he said.

On the corner of Robinson’s desk, sits a bust of a man very closely resembling Robinson himself. His friend sculpted this bust for him after Robinson was the hand and face model for the statue of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit Order, whose statue sits in front of Boston College’s Tip O’Neill Library. Sculptor Pablo Eduardo created the statue, a 13-foot tall figure with features just like Robinson’s. “I’m sort of going to be immortal,” he said.