Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Woof Magazine.

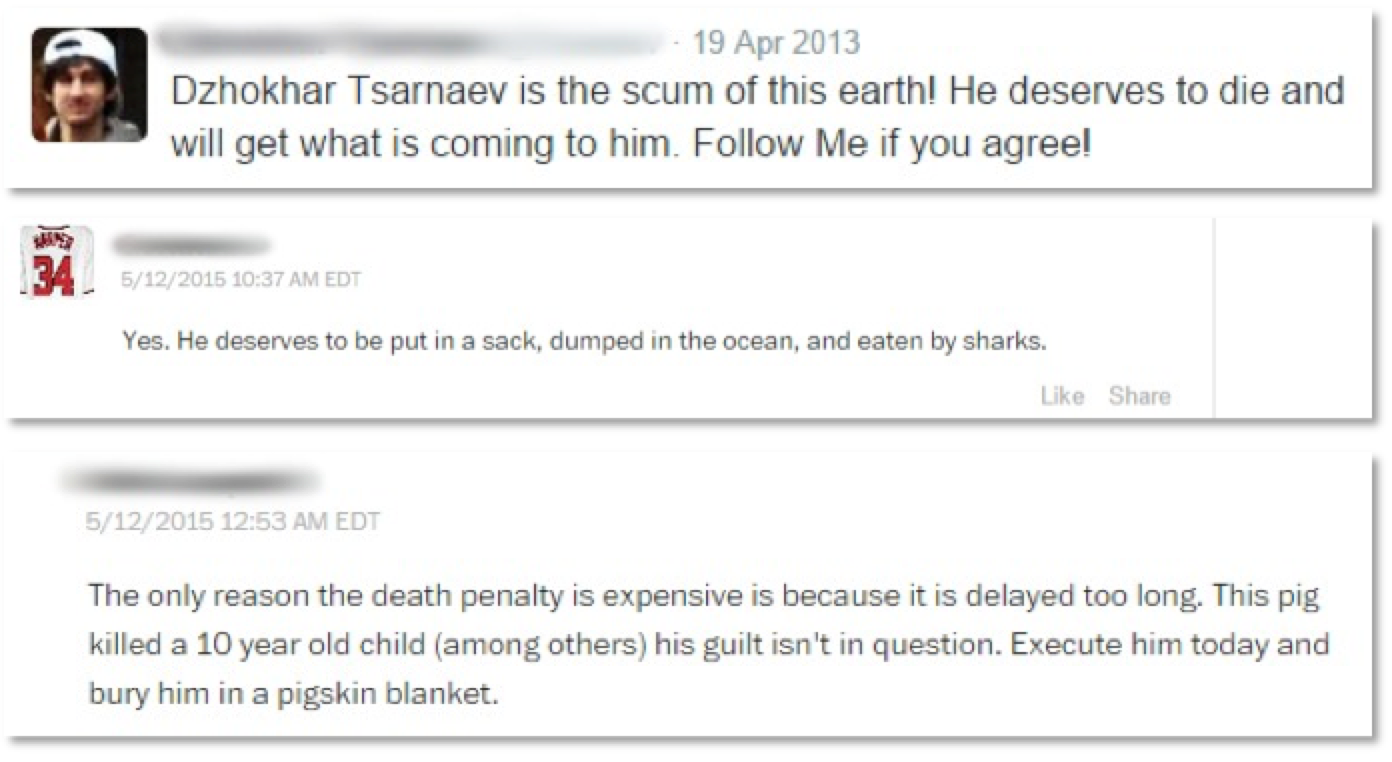

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the 21-year old University of Massachusetts Dartmouth student who committed the 2013 Boston Bombings, was sentenced to death on Friday, May 15th. In the days leading up to the verdict, people across all social media outlets were debating and guessing at what his verdict would be. In every discussion that I saw, people were crying for Tsarnaev’s blood. They wanted him to “get what he deserved,” whether that meant life imprisonment, a lethal injection, or some other punishment thought up by whoever happened to be behind the screen name. The abundance of these messages was astounding; people that I personally knew would never hurt a fly were suddenly up in arms and crying out for the suffering of a 21-year old boy with the only attempt at justification being the ubiquitous label of justice.

The desperation with which people were crying for Tsarnaev to be punished and for “the right thing to be done” was powerful enough to suggest that, somehow, Tsarnaev being locked in a room alone for 23 hours a day for the rest of his life could reunite grieving families with their loved ones. But Tsarnaev’s punishment, no matter how cathartic it would be to those thirsting for blood, will not bring grieving families happiness, and it will not stop terror attacks from occurring again. The only way to make significant progress towards the prevention of this violent mentality is by acknowledging that mentality, admitting that something is wrong and accepting that something needs to change.

To clarify before continuing, I am not calling Tsarnaev innocent. I am not condoning what he did, nor am I suggesting that he should not be punished. He did a horrible, horrible thing, and terror attacks such as his should always be followed by the prosecution of the orchestrator. What I am discussing is the mentality that follows attacks like this and the instantaneous change from a peaceful society to one that can, in a manner that suddenly becomes socially acceptable, fight for the death of a 21-year old boy. What I am discussing is the almost imperceptible change in mindset that demonizes this 21-year old boy and turns him into a monster to lock in a box until it dies.

Tsarnaev’s Wikipedia picture is one of him in jail because that’s what people want to see. People do not want to see how young he really looks; they do not want to see how he could be their son or their brother or their friend. People want to have their primitive, animalistic thirst for revenge justified, and so Dzhokhar Tsarnaev becomes demonized. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev loses the fact that he is someone’s son and someone’s brother; he loses the fact that he was ever human at all. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev becomes an idea: the death of four people and the terror experienced by an entire country. And, quite instantaneously, he thus becomes okay to wish harm upon. Any attempts at reformation or empathy go out the window, because his identity is now a murderer, and murderers can’t be helped.

An important distinction that I want to make, before continuing, is that I am not absolving Tsarnaev of personal responsibility. He is a fully functioning, cognizant, self-aware human being with full control over his own actions. But having full control over one’s actions does not eliminate the subjectivity of knowing what is right and what is wrong; morality is based on experiences, and a human cannot act in such a way to account for information that he does not have. To Tsarnaev, his choices were acceptable because of the life that he’s lived. He might accept that murder is wrong, but he also might believe that retaliation is justice. Yet, just because I say that Tsarnaev is not inherently evil, does not mean that I am taking away his personal responsibility; he still did horrible things, and he should still pay the price.

Tsarnaev wasn’t born holding the bombs to place on Boylston Street. He wasn’t born holding the gun that shot the police officer chasing him. He was given these things, and he learned the behaviors that threw him into the situation in which he found himself. Because of the environment in which he was immersed – a tumultuous, chaotic collision of a fundamentalist mother, a “violent jihadist” brother and a father with “severe psychiatric disorders”- he believed that his sole choice, and thus his purpose, was to commit an act of terror (1).

No one is born inherently wanting to commit mass atrocities; a person learns that over time. And someone in Tsarnaev’s situation, lacking direction and vulnerable to a fanatical push towards violence will never attempt to seek help because society, as proven by people’s reactions, will not understand. Society, as shown by the backlash of the Bombings, will yell at you and curse at you and cry for the death of you and everyone you love. Society won’t try to help you, because you’re no longer a person; you’re a monster whose life no longer contains value.

The historic trend of responding to terror attacks with violence does nothing but further isolate the people who are susceptible to these behaviors. And the most ironic part about the theft of an individual’s humanity is the proportional degradation of our own. As we cheer on the death of a boy, we become the monsters that we are trying to eradicate. Our humanity is deafened by our cries for blood, and our cries do nothing but add to the positive feedback loop of violence. We’ve managed to justify the murder of a boy; how can we come back from that? Using violence as a deterrence to violence is a fundamentally flawed system that only results in a world of monsters. The public needs to look at this situation from a contextual point of view and try to separate emotions from the justice process.

The practical difficulty in implementing this idea in the real world is the willingness of the public to let go of reason and embrace blind rage. A terror attack is taken as a personal affront; it is interpreted as an underhanded attack on one’s home, on the place where one is supposed to feel the most secure. This misinterpretation is what breeds the violent mentality and thirst for retaliation… Reason loses all relevance in the heat of the violent mentality.

Consider it on a smaller scale. Imagine you get punched in the face. Your assailant tells you exactly why he did it, but you don’t understand. You can’t understand because you are a different person with different experiences and a different perception of the world. To you, his reasons are ridiculous, and his explanation is just an excuse to punch someone. So you punch him back. You’re angry, and you lash out. You try to restore balance to the world by returning his misdeed. But your punch will never change his mind. Your punch will not stop him from wanting to punch people and it will not stop his brother from wanting to punch people and it will not stop people from wanting to punch people. Your reaction does nothing but encourage violence without ever addressing or attempting to understand why he punches people. This instinctual, animalistic reaction to violence is the biggest hurdle stopping us from addressing the real issue and preventing future brutality. If humans are trying to eliminate violence, retaliation is not the method for doing so. A punch for a punch is a net of two punches, not zero. And violent tendencies, when left unchecked, do nothing but fan their own flames.

Going against the violent tendencies is not easy. Violence is ingrained in every fiber of our being; the majority of our Genus’s history has been lived in that half-second between life and death where violence is the only solution to living another day. This instinctual violence is still locked in the reptilian portion of our brains that pushes us away from logic and reason and towards blind aggression (2). But the acknowledgement of this tendency’s existence is not a submission to its will. We, as a species, need to recognize our predisposition for violence. We need to recognize that, despite our natural inclination towards savagery, we have the power to act with civility and understanding. Our instincts may not be easy to overcome, but, with constant cognizance, we will be able to combat this violent mentality and become the pinnacle of civil society for which we claim to be striving.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is an illustration of why we need to rid ourselves of this violent mentality. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is an example of how easily a society can go from civilized to barbaric in the blink of an eye. The thorough dehumanization of Dzhokhar is incredible. And this dehumanization is what I’m addressing in this article. If we truly want to end violence, we need to understand people as humans. We need to understand that murderers and terrorists and bullies are all groomed to hold a certain mindset, but they are all still people. We are not justifying their wrongdoings, nor are we making excuses for their behavior. Instead, we are recognizing their humanity in order to preserve our own. Catharsis is not justice, and we need to respect the humanity of those we hate the most or risk losing our own.

Have a counterargument or additional thoughts? We want to hear it! You can submit your own argument to nuwoof@gmail.com.

Supporting articles:

2. http://teacher.scholastic.com/professional/bruceperry/aggression_violence.htm