Desire is one of the most intricate elements of the human experience. With every passing day, we are tasked with navigating the murky waters of introspection, grappling with the tension between what we think we want, what we truly desire and the carefully curated image of ourselves we present to the world. Halina Reijn’s “Babygirl” brings this struggle to center stage, exploring the complexities of sexuality through a journey of self-discovery.

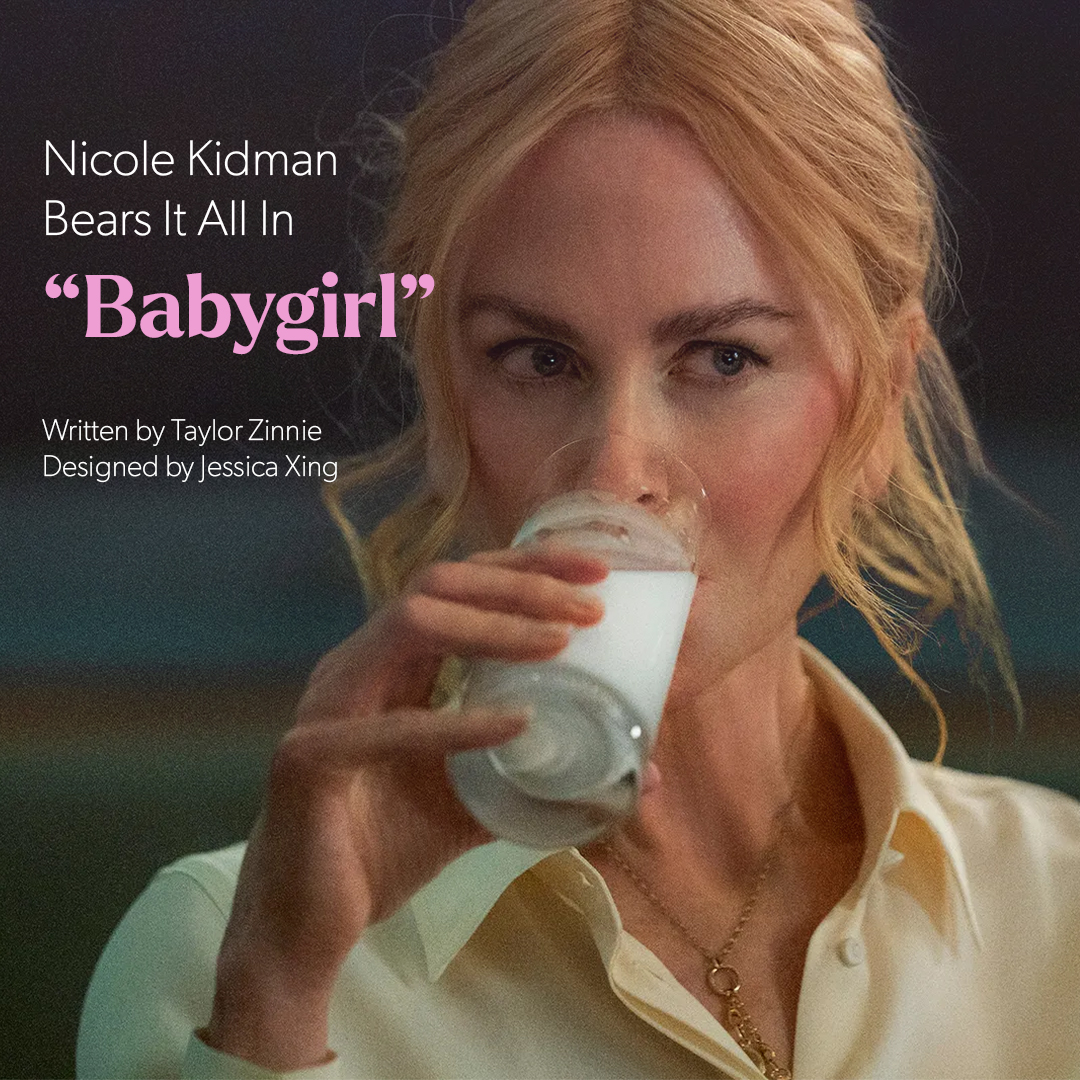

Released in theaters on Dec. 25, 2024, “Babygirl” stars Nicole Kidman as Romy Mathis, founder and CEO of a warehouse automatic robotics company. Living what appears to be a picture-perfect life, Romy has it all: a career at its peak, a loving husband and two beautiful daughters. However, beneath the surface of her seemingly flawless existence, Romy is experiencing a disconnect, with her sexuality being the one area in which she has never found fulfillment. Enter Samuel, played by Harris Dickinson. He initially catches Romy’s attention on the streets of New York City during her commute to work, when she watches him assuredly tame an off-leash dog, exuding a sense of command that captivates her. Later that day, she discovers he is among the new class of interns working in her office.

The character of Samuel ignites an internal conflict within Romy, forcing her to confront not only the reality of her suppressed erotic desires but also the dissonance between those desires and her expected role in society. As an emblem of authority, Romy is used to being in control. Yet, Samuel’s unusual lack of blind deference challenges this expectation, undermining her sense of power in a way that she has been longing for. He is bold and direct, treating her not as his superior but as an equal. In their first private encounter, Samuel pushes boundaries by explicitly suggesting that Romy enjoys being told what to do. His behavior entices her, eventually igniting a clandestine affair that allows Romy to explore her desire for submission. As the relationship intensifies, she becomes addicted to it, struggling to balance her growing impulses with the responsibilities of her home life.

“Babygirl” offers an intriguing examination of sexuality and pleasure, presenting a case study that feels both provocative and deeply genuine. The film’s genius lies in its authenticity, with portrayals that bring raw, nuanced characters to life leaving a lasting impression. The narrative is straightforward and lacks complexity, which may come across as one-dimensional but ultimately enhances its realism. The film revolves around the affair with little else driving the story, but therein lies its beauty; absent elaborate plot twists, the simplicity allows the raw truth of the narrative to take center stage.

The performances from Kidman and Dickinson add profoundly to the way this movie resonates with viewers, curating a dynamic that is not solely sultry but tense and real. Kidman and Dickinson’s performances elevate the film, curating a dynamic that feels awkward yet organic, subverting expectations for an erotic thriller. In a culture where depictions of sex in media often rely on shock value, overly sultry and salacious to the point of feeling inauthentic, “Babygirl” strikes the right balance, offering a portrayal that feels authentic and true to life. Nervous energy, awkward pauses and hesitation add layers of depth and realism to the characters’ connection, making it all the more compelling.

The plot of a torrid affair is far from innovative, and it is easy to dismiss “Babygirl” as just another addition to the overdone genre. From “Gone Girl” to “How To Get Away With Murder,” the trope of an older spouse entering an illicit romance with a young new prospect has consistently consumed screens. However, the film dives deeper, reinventing power dynamics and exploring the social pressures that dictate how women approach sexuality and desire. While infidelity is never moral, Romy’s relationship with Samuel serves as a vessel for liberation; a brief escape from the constraints and expectations of her everyday life. This nuanced perspective can be partially credited to having a woman in the director’s chair. Reijn masterfully captures how conformity and docility in all aspects of life can prevent women from fully experiencing pleasure, all while avoiding outdated clichés rooted in misogyny. Through Romy’s journey, the audience witnesses how the safety of a picture-perfect, picket-fence life is often what women are expected to strive for, yet leaves a void of true fulfillment.

Society scrutinizes sex and pleasure so harshly that female desire can become intertwined with shame. In a refreshing instance of a female filmmaker being granted the freedom to create provocative and thought-provoking media, Reijn challenges viewers to confront themes often regarded as taboo. “Babygirl” isn’t comfortable — it is bound to elicit some awkward giggles and certain scenes may be hard to watch without blushing. However, this discomfort only makes the story more worthy of being told.

While its underlying concepts make it worth the watch, “Babygirl” is not a movie that can easily be revisited, and it might even be difficult to call entertaining in the traditional sense. However, the film leaves a profound and lasting impact, delivering a raw story of self-discovery. “Babygirl” is more commendable than enjoyable, but still pushes the envelope in a way that demands applause.